© 2013, NVIDIA CORPORATION. All rights reserved.

Code and text by Sean Baxter, NVIDIA Research.

(Click here for license. Click here for contact information.)

Latency-oriented systems (CPUs) use large caches, branch prediction, and speculative fetching to avoid stalls on data dependencies. GPUs, by contrast, are throughput-oriented systems that use massive parallelism to hide latency. Occupancy is a measure of thread parallelism in a CUDA program. Instruction-level Parallelism is a measure of parallelism within threads. The higher the occupancy and ILP, the more opportunities an SM has to put compute and load/store units to work each cycle. Threads waiting on data dependencies and barriers are taken out of consideration until their hazards are resolved.

Kernels may be limited by DRAM to L2 cache bandwidth, L2 to SM bandwidth, texture bandwidth, FFMA, DFMA, integer, or shared memory performance. In some sense, being limited by bandwidth is a victory condition for optimization: a routine is fully exploiting at least one capability of the device. Performance can then only be improved by redesigning the code to use less of the limiting resource.

More often, and especially for codes that involve many subsystems, a kernel is latency limited. This state of under-occupancy occurs when there is insufficient parallelism to hide instruction latency. Many highly-optimized routines become latency limited as work efficiency improves. As code becomes leaner the GPU has more free units than it has instructions to execute, a consequence of optimizing away unnecessary operations.

Important: The performance of latency-limited kernels is difficult to reason about. Optimizations that reduce work (or improve work efficiency) might not improve—and could even hinder—throughput. Focus on reducing latency on the most-congested path.

There are five resource limits that cap occupancy:

| sm_20 | sm_30 | sm_35 | |

| Max Threads (SM) | 1536 | 2048 | 2048 |

| Max CTAs (SM) | 8 | 16 | 16 |

| Shared Memory Capacity (SM) | 48 KB | 48 KB | 48 KB |

| Register File Capacity (SM) | 128 KB | 256 KB | 256 KB |

| Max Registers (Thread) | 63 | 63 | 255 |

Max Threads - You may be under-occupied even with 100% occupancy (1536 or 2048 threads running concurrently per SM). This is likely caused by poor ILP: increase the program's parallelism by register blocking to process multiple elements per thread. In MGPU most kernels are register blocked with grain size VT. You may also want to reduce the CTA size, so that barriers don't stall as many threads: smaller CTAs lead to better overlapped execution than larger ones.

Max CTAs - If you launch small blocks, your occupancy will be constrained by a hardware limit on resident CTAs. On Kepler, blocks must be at least 128 threads wide to hit maximum occupancy (16 CTAs/SM). Using smaller blocks reduces occupancy; larger blocks compromise overlapped execution. In the absence of performance data, start with blocks of 128 or 256 threads.

Shared Memory Capacity - Many optimized register-blocked kernels are limited by shared memory capacity. Fermi has a 2.7:1 ratio of register file to shared memory. Kepler SMs have higher arithmetic throughput and latency (the two often increase together), but hasn't increased shared memory capacity, giving a ratio of 5.3:1. At 100% occupancy, a thread has 32 registers (128 bytes) but only 24 bytes of shared memory. Register blocking for eight values per thread, with shared memory sized to accommodate all the values at once (for key exchange and other critical operations), implies no higher than 1536 threads/SM occupancy (75%). More aggressive register blocking drops this further. Operating at less than maximum occupancy does not imply under-occupancy, as ILP may be sufficient to cover latencies.

Register File Capacity - Register file is more copious than shared memory, and in the inverted cache hierarchy that GPUs are designed with, it's larger than even L2 cache. Still, code may be limited by RF capacity. Do mental live analysis while writing your kernel to reduce register usage. If your kernel uses more registers than you expect, try re-ordering load and store procedures to move out results before reading more inputs.

Max Registers - sm_20 and sm_30 devices have a limit of 63 registers per thread. If the back-end code generator cannot fit the working set of the kernel into 63 registers, it provisions local memory (driver-managed global memory) to spill state. Kernels with spill assume additional latency. sm_35 devices have access to 255 registers per thread. While this relieves a register pressure problem for many procedures, it may also cause an additional drop in occupancy. sm_30 kernels that are limited by RF capacity will run at 50% occupancy (63 registers/thread). The same kernel running on sm_35 may only achieve 12.5% occupancy, because each thread now consumes four times as much of the RF.

For all performance-critical kernels, compile with -Xptxas="-v". This passes a request through the NVVM compiler to the PTX assembler to output register, shared memory, and spill information for all kernels on each target architecture.

ptxas : info : Compiling entry function 'KernelFoo' for 'sm_20'

ptxas : info : Function properties for KernelFoo

48 bytes stack frame, 48 bytes spill stores, 36 bytes spill loads

ptxas : info : Used 63 registers, 11264 bytes smem, 64 bytes cmem[0]

ptxas : info : Compiling entry function 'KernelFoo' for 'sm_35'

ptxas : info : Function properties for KernelFoo

0 bytes stack frame, 0 bytes spill stores, 0 bytes spill loads

ptxas : info : Used 80 registers, 11264 bytes smem, 352 bytes cmem[0]

The above kernel is too-aggressively register blocked. It hits the 63 register limit and spills on Fermi, achieving 25% occupancy. The function on Fermi is limited by RF capacity - launching four 128-thread CTAs consumes the entire register file.

Because of sm_35's per-thread register increase, the same code doesn't spill on GK110 Kepler. Thanks to the doubled RF capacity, it not limited by that, either. However, the code still runs at only 25% occupancy, because it's limited by shared memory capacity. Each CTA uses 11KB of shared memory, and since the SMs only have 48KB to share, only four 128-thread CTAs may be scheduled per SM (25% occupancy).

ptxas : info : Compiling entry function 'KernelFoo' for 'sm_20'

ptxas : info : Function properties for KernelFoo

0 bytes stack frame, 0 bytes spill stores, 0 bytes spill loads

ptxas : info : Used 48 registers, 6144 bytes smem, 64 bytes cmem[0]

ptxas : info : Compiling entry function 'KernelFoo' for 'sm_35'

ptxas : info : Function properties for KernelFoo

0 bytes stack frame, 0 bytes spill stores, 0 bytes spill loads

ptxas : info : Used 48 registers, 6144 bytes smem, 352 bytes cmem[0]

Reducing the grain size VT improves occupancy by tackling less work per thread, requiring less state, and thereby consuming less resource. Five CTAs per SM are scheduled on Fermi - the kernel is RF capacity limited (five kernel use 30720/32768 registers). Both sm_30 and sm_35 fare better here. Eight CTAs are scheduled per SMX, limited by shared memory capacity (eight CTAs use all 49152 bytes).

Important: If a kernel spills even after you decrease grain size, you may be inadvertently dynamically indexing into an array that you intended to have reside in register. Use only literals, constant expressions, and unrolled loop iterators to index into register arrays. A compiler warning about an "unknown pragma" that refers back to a #pragma unroll attribute indicates that some construct is preventing the loop from unrolling, turning static indexes into dynamic ones, and likely causing spill. Although spilling may help performance by increasing occupancy in complex kernels, you should never allow spill that's caused by inadvertent dynamic indexing; this always hurts performance.

CTA size and shared memory consumption are specified by the programmer; these are easily adjusted. RF usage, on the other hand, is a consequence of choices made by the register allocator in the back-end code generator. The __launch_bounds__ kernel attribute gives the user more control over occupancy by providing a cap on per-thread register usage. Tag the kernel with the CTA size and the desired number of CTAs per SM. The code generator now caps register usage by re-ordering instructions to reduce live variables. It spills the overflow.

ptxas : info : Compiling entry function 'KernelFoo' for 'sm_20'

ptxas : info : Function properties for KernelFoo

40 bytes stack frame, 40 bytes spill stores, 24 bytes spill loads

ptxas : info : Used 36 registers, 6144 bytes smem, 64 bytes cmem[0]

ptxas : info : Compiling entry function 'KernelFoo' for 'sm_35'

ptxas : info : Function properties for KernelFoo

0 bytes stack frame, 0 bytes spill stores, 0 bytes spill loads

ptxas : info : Used 48 registers, 6144 bytes smem, 352 bytes cmem[0]

The previous tuning of KernelFoo was tagged with __launch_bounds__(128, 7) to guarantee that 7 CTAs run on each SM. The function now spills on Fermi, but uses only 36 registers per thread (32256/32768 registers per SM). The generated code is unchanged on Kepler, which remains limited to 8 CTAs/SMX by shared memory capacity.

Most MGPU kernels are parameterized over NT (number of threads per CTA) and VT (values per thread, the grain size). The product of these two, NV (number of values per CTA), is the tile size. Increasing tile size amortizes the cost of once-per-thread and once-per-CTA operations, improving work efficiency. On the other hand, increasing grain size consumes more shared memory and registers, reducing occupancy and the ability to hide latency.

The constants NT, VT, and the __launch_bounds__ argument OCC (for occupancy, the minimum number of CTAs per SM) are tuning

parameters. Finding optimal tuning parameters is an empirical process. Different hardware architectures, data types, input sizes and distributions, and compiler versions all effect parameter selection. User-tuning of MGPU library functions may improve throughput by 50% compared to the library's hard-coded defaults.

template<typename GatherIt, typename ScatterIt, typename InputIt,

typename OutputIt>

MGPU_HOST void IntervalMove(ScatterIt scatter_global, const int* scan_global,

int intervalCount, int moveCount, InputIt input_global,

OutputIt output_global, CudaContext& context) {

const int NT = 128; // Hard-coded MGPU defaults

const int VT = 7;

...MGPU library functions have hard-coded and somewhat arbitrary parameters. The tuning space for type- and behavior-parameterized kernels is simply too large to explore in a project with Modern GPU's goals and scope.

// Copy and modify the host function to expose parameters for easier tuning.

template<int NT, int VT, int OCC, typename GatherIt, typename ScatterIt,

typename InputIt, typename OutputIt>

MGPU_HOST void IntervalMove2(ScatterIt scatter_global, const int* scan_global,

int intervalCount, int moveCount, InputIt input_global,

OutputIt output_global, CudaContext& context) {

// Parameters NT, VT, and OCC are passed in and override the host

// defaults.

...Identify performance-critical routines and the contexts from which they are invoked. Copy the MGPU host functions that launch the relevant kernels and edit them to expose tuning parameters to the caller. Run the code on actual data and deployment hardware through the included benchmark programs, testing over a variety of parameters, to understand the performance space. Use the optimal settings to create specialized entry points to get the best throughput from your GPU.

Important: The omnipresent grain size parameter VT is almost always an odd integer in MGPU code. This choice allows us to step over bank-conflict issues that would otherwise need to be resolved with padding and complicated index calculations. Kernels execute correctly on even grain sizes, but expect diminished performance on these. Omit even grain sizes when searching the tuning space.

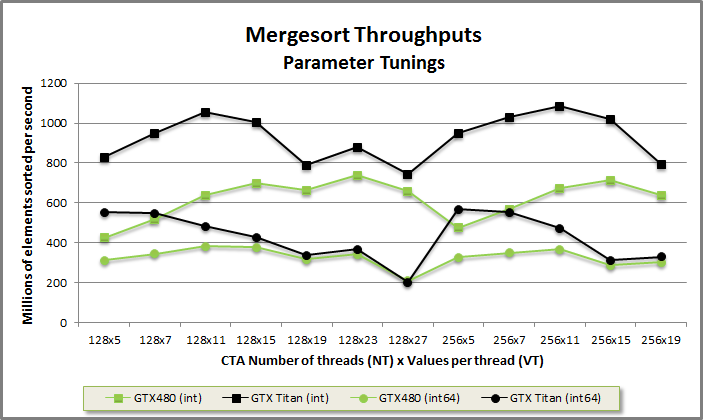

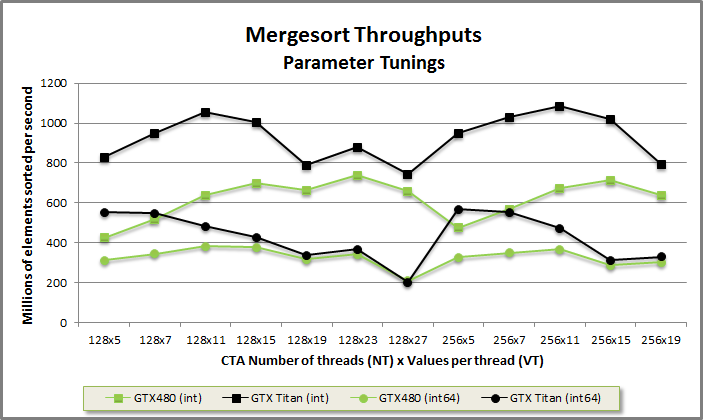

Mergesort tuning benchmark from benchmarklaunchbox/benchmarklaunchbox.cu

We've benchmarked MGPU's keys-only mergesort on GTX 480 and GTX Titan, specialized for both 32- and 64-bit integer types. You can see the function's sensitivity to tuning parameters. Note the best-performing configurations for each device and data-type:

| GTX 480 (Fermi) | GTX Titan (Kepler) | |

| 32-bit int | 128x23 | 256x11 |

| 64-bit int | 128x11 | 256x5 |

Parallelism (occupancy) decreases and work-efficiency increases as the grain size goes up. Kepler parts require much higher occupancy than Fermi to reach top performance—the SM is much wider (6 FFMA units up from 2 on Fermi), but per-SM shared memory remains the same at 48KB, badly underoccupying the device at larger grain sizes. Because Fermi runs well at lower occupancy, it benefits from scheduling 128-thread blocks, even at the cost of an additional merge pass. Smaller blocks improve effective occupancy by stalling fewer threads at a synchronization.

Due to the GPU's raw power even untuned codes run excellently, often an order-of-magnitude beyond what you can achieve on the CPU. Tuning benchmarks may be the easiest way to squeeze 20-30% out of your code. It also informs the programmer of the performance landscape, leading to more productive profiling if they decide to go the extra mile. It's always good to tune before profiling so that you don't waste time optimizing code just to get to a local maxima.

Important: The hard-coded tuning parameters for MGPU functions were selected for decent performance on large arrays of 32- and 64-bit data types running on Kepler architecture. Users targeting Fermi devices may want to increase grain sizes significantly, as codes on that generation run better at lower occupancies. In all cases, finding optimal tuning parameters for specific data types and distributions, input sizes, and architectures, is the easiest way to improve performance of well-written code.

Once suitable tuning parameters have been discovered, specialize the host functions over data type (with function overloading or partial template specialization) and input size (with a runtime check and multiple launches). Specializing tuning parameters for different device architectures is more difficult.

The NVCC front-end strips out __device__ and __host__ tags. It calls the host compiler (Visual C++ or GCC) once for the host code and invokes the NVVM back-end once for each architecture. If we were to specialize tuning for each device by branching over compute capability (determined at runtime with cudaDeviceProp::major and minor) and making a different chevron launch for each one, we'd end up compiling the cross product of all tunings over all architectures. Even though an sm_20 client will never actually launch kernels specialized with sm_30 or sm_35 tunings, that code would still be included with your binary because the multi-pass build process can't use dead code elimination on launches contingent on a runtime check.

CUDA defines a __CUDA_ARCH__ macro for the compute capability of the architecture that is currently being built in the multi-pass system. Although this macro is not available to the host at runtime, it can be used from inside a kernel's source to allow the kernel to change its own behavior. The macro is typically used to let a kernel opt into features that aren't available on all devices: e.g. the popc instruction counts the set bits in word, replacing a loop, when __CUDA_ARCH__ >= 200. We use this macro to guide the build process and only generate device code for the architectures it will run on.

MGPU introduces LaunchBox, a structure that specializes kernels for different compute capabilities without generating the cross product of each parameterization and architecture. Think of LaunchBox as concatenating the tuning parameters for all architectures into a single type and specializing the kernel over that type. The kernel reads the relevant parameters from the LaunchBox and changes its own implementation accordingly.

// LaunchBox-specialized kernel Foo uses MGPU_LAUNCH_BOUNDS kernel to control

// register usage. The typename Tuning is obligatory, and must be chosen for

// the MGPU_LAUNCH_BOUNDS and MGPU_LAUNCH_PARAMS macros to work.

template<typename Tuning>

MGPU_LAUNCH_BOUNDS void Foo() {

typedef MGPU_LAUNCH_PARAMS Params;

if(!blockIdx.x && !threadIdx.x)

printf("Launch Foo<<<%d, %d>>> with NT=%d VT=%d OCC=%d\n",

gridDim.x, blockDim.x, Params::NT, Params::VT, Params::OCC);

}

// Use the built-in LaunchBoxVT type to specialize for NT, VT, and OCC.

void LaunchFoo(int count, CudaContext& context) {

typedef LaunchBoxVT<

128, 7, 4, // sm_20 NT=128, VT=7, OCC=4

256, 9, 5, // sm_30 NT=256, VT=9, OCC=5

256, 15, 3 // sm_35 NT=256, VT=15, OCC=3

> Tuning;

// GetLaunchParamaters returns (NT, VT) for the arch vesion of the provided

// CudaContext. The product of these is the tile size.

int2 launch = Tuning::GetLaunchParams(context);

int NV = launch.x * launch.y;

int numBlocks = MGPU_DIV_UP(count, NV);

Foo<Tuning><<<numBlocks, launch.x>>>();

}Opt into LaunchBox by templating your kernel over Tuning (Tuning is an obligatory name). The MGPU_LAUNCH_BOUNDS macro, which includes the __global__ tag, generates the __launch_bounds__ attribute with the NT and OCC parameters specified at the launch site. The macro uses __CUDA_ARCH__ to discriminate between compute capabilities, binding to the static values corresponding to the currently-executing NVVM compiler pass. Typedef the MGPU_LAUNCH_PARAMS macro to access the tuning parameters inside the kernel.

Use LaunchBox to specialize the mergesort benchmark above:

Specialize 32-bit mergesort for Fermi and Kepler with LaunchBoxVT<128, 23, 0, 256, 11, 0>.

Specialize 64-bit mergesort for Fermi and Kepler with LaunchBoxVT<128, 11, 0, 256, 5, 0>.

These tunings for sm_20 and sm_30 are inherited by other platforms (sm_21 inherits sm_20; sm_35+ inherits sm_30). We choose not to constrain register count by leaving the occupancy parameter zero.

Most users will only need the LaunchBoxVT structure, a specialization that makes tuning more succinct. Specialize this template over (NT, VT, OCC) for sm_20, sm_30, and sm_35. Default template arguments inherit parameters from the earlier-generation architecture, so LaunchBoxVT<128, 7> is equivalent to LaunchBoxVT<128, 7, 0, 128, 7, 0, 128, 7, 0>.

Use the static method GetLaunchParams, passing the CudaContext object, to return the (NT, VT) arguments for the compute capability of the currently-selected device. The product of these is the tile size. Use it to calculate the launch's grid size. Finally, specialize the kernel over Tuning and launch the grid with launch.x (NT) threads.

// LaunchBox-specialized kernel Bar introduces its own set of launch parameters.

template<int NT_, int VT_, int OCC_, int P1_, typename T1_>

struct BarParams {

enum { NT = NT_, VT = VT_, OCC = OCC_, P1 = P1_ };

typedef T1_ T1;

};

template<typename Tuning>

MGPU_LAUNCH_BOUNDS void Bar() {

typedef MGPU_LAUNCH_PARAMS Params;

if(!blockIdx.x && !threadIdx.x) {

printf("Launch Bar<<<%d, %d>>> with NT=%d VT=%d OCC=%d\n",

gridDim.x, blockDim.x, Params::NT, Params::VT, Params::OCC);

printf("\t\tP1 = %d sizeof(TT1) = %d\n", Params::P1,

sizeof(typename Params::T1));

}

}

void LaunchBar(int count, CudaContext& context) {

typedef LaunchBox<

BarParams<128, 7, 4, 20, short>, // sm_20

BarParams<256, 9, 5, 30, float>, // sm_30

BarParams<256, 15, 3, 35, double> // sm_35

> Tuning;

int2 launch = Tuning::GetLaunchParams(context);

int nv = launch.x * launch.y;

int numBlocks = MGPU_DIV_UP(count, nv);

Bar<Tuning><<<numBlocks, launch.x>>>();

}LaunchBoxVT inherits the more generic LaunchBox type and provides some syntactic sugar. LaunchBox takes three types as arguments and typedefs those to Sm20, Sm30, and Sm35. When devices based on the Maxwell architecture are released, LaunchBox will add additional typedefs. The LaunchBox technique inherits parameter tunings to avoid versioning difficulties. Although LaunchBox puts no restrictions on its specialization types, constants NT and VT must be included if the host code wishes to use LaunchBox::GetLaunchParams (the client can elect not to use this), and NT and OCC must be included to support MGPU_LAUNCH_BOUNDS (ditto).

GeForce GTX 570 : 1464.000 Mhz (Ordinal 0)

15 SMs enabled. Compute Capability sm_20

FreeMem: 778MB TotalMem: 1279MB.

Mem Clock: 1900.000 Mhz x 320 bits (152.000 GB/s)

ECC Disabled

Launching Foo with 1000000 inputs:

Launch Foo<<<1117, 128>>> with NT=128 VT=7 OCC=4

Launching Bar with 1000000 inputs:

Launch Bar<<<1117, 128>>> with NT=128 VT=7 OCC=4

P1 = 20 sizeof(TT1) = 2Launching Foo and Bar prints the above. The host function correctly coordinates the launch with the statically- specialized kernel.

There is one small caveat: if LaunchBox is used to specialize kernels for architectures that are not compiled with -gencode on the command line, LaunchBox::GetLaunchParams could return a different set of tuning parameters than those that the kernel actually gets specialized over. If, for example, the program is compiled for targets sm_20 and sm_30 but is executed on an sm_35 device, the kernel that is launched would be for sm_30 (the largest targeted architectured not greater than the architecture of the device), however the host side would configure the launch with the tuning parameters for sm_35.

To properly coordinate between the static device-side and dynamic host-side interfaces, we implement GetLaunchParams so that it uses the highest targeted architecture not greater than the device's compute capability when selecting dynamic launch parameters.

// Returns (NT, VT) from the sm version.

template<typename Derived>

struct LaunchBoxRuntime {

static int2 GetLaunchParams(CudaContext& context) {

int sm = context.CompilerVersion();

if(sm < 0) {

cudaFuncAttributes attr;

cudaFuncGetAttributes(&attr, LBVerKernel);

sm = 10 * attr.ptxVersion;

context.Device().SetCompilerVersion(sm);

}

// TODO: Add additional architectures as devices are released.

if(sm >= 350)

return make_int2(Derived::Sm35::NT, Derived::Sm35::VT);

else if(sm >= 300)

return make_int2(Derived::Sm30::NT, Derived::Sm30::VT);

else

return make_int2(Derived::Sm20::NT, Derived::Sm20::VT);

}

};The first time GetLaunchParams is called, CudaDevice::CompilerVersion is unset, and we call cudaFuncGetAttributes on a place-holder method LBVerKernel. (Although it is never launched, taking the address of this kernel keeps it in our program.) This bit of CUDA introspection returns the target architecture of the compiled kernel (and presumably all other kernels in the program) through cudaFuncAttributes::ptxVersion. LaunchBox allows the CUDA runtime to coordinate the host and device sides of the call. All subsequent LaunchBox invocations are ready to go with the compiler version.